Roman Sompolinski: The Untold Story of a Holocaust Survivor

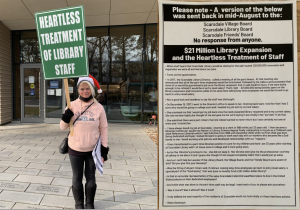

Roman Sompolinski and his wife, Masza, in the displaced persons camp.

May 8, 2022

***Trigger Warning: article contains some graphic descriptions that some may find disturbing.***

His name at birth was Riven Sompolinski. He was born on January 3, 1923, in Zgierz, Poland, a business town that was 40% German, 55% Polish, and 5% Jewish. His father, Jacob, was a businessman who owned a textile factory and flour mill. Roman would enjoy going to his dad’s textiles factory to see the machines. Throughout his youth, he loved to take apart bicycles and machines to see how they would work and then reassemble them. His mother, Sura, had a friend with no children who owned two movie theaters in town. Her friend let Roman work at the theater projecting the films and operating the camera. He was told he would own theaters when he grew up.

He had a sister named Bella, who had three children. Bella and her family did not survive. He also had four brothers, Benjamin, then Baruch, Slomo, and Abraham. None of them survived. His family was modern orthodox. He had a bar mitzvah with his family and friends. His family belonged to the Macabee in Zgeirz. They swam, biked, hiked, and played soccer. Life was good, until it wasn’t.

Anti-Semitism significantly increased in 1937. Pritzger, a local politician, introduced a bill to make kashrut, or kosher eating, criminal, but it did not pass. A Polish newspaper took pictures of Poles who bought goods at Jewish stores in an attempt to make people stop buying from them. Some Jews were victims of bullying and were beaten up for their religion. Roman’s family couldn’t get visas to emigrate. They were trapped.

When the Germans came to his town, they further attacked the Jews and stole their belongings. The textile company that he enjoyed going to with his father as a child was taken away. They were told that if they didn’t leave they would be executed. In December of 1940, at the age of sixteen, Roman was peacefully walking on the street and the Nazis took him and shipped him to Germany to work. He never got the chance to say goodbye to his family. They did not know where he went.

After a long ride, Roman arrived in Britz, a working camp. The Nazis were building the Berlin-Warsaw-Moscow Autobahn. He worked there from 1940 to 1942. They had little food – bread, coffee, and soup. He worked for 11 hours a day, and when Auschwitz needed young people to work, he was shipped there in May of 1943.

At the platform, he saw 30,000 people, including two of his brothers. Roman and his brothers waved to each other, but they couldn’t get close. Later on, his brothers were sent to the gas chambers. He never saw them again. He then had to go to the selection to see who would work and who would be gassed to death. Roman was sent to work.

His job was to undress the dead and take their valuables. The Nazis would kill you if you showed any emotion, so he kept working through the pain. As he said, there was no humanity there. After four weeks he was tattooed on his left arm. He was nothing more than a number. He was put in a barrack that had about 180 men. In 1944, they checked his tattoo. He didn’t want to redo his tattoo because he wanted to try to escape. In response, they broke his ribs and he ended up in the hospital.

A year later, he went with three men to the kitchen and saw rotten potatoes on the ground. What was garbage to the Germans was food for the barracks. Commandant Josef Kramer, the butcher of Bergen-Belsen, saw them and shot the other two boys to death. Kramer shot Roman for having a potato in his hand. He blacked out.

When he woke up, he was in a clean bed with white sheets. The British Army liberated them on April 15, 1945. Many survivors died because the British gave people food that was too rich for people who were malnourished for years. He was twenty-two years old at liberation and weighed only sixty-nine pounds.

At the Belsen Trial, he met many people from the United States and the United Kingdom, including General Montgomery, the most senior general in the British Army. The general asked him why he did not stand up against Kramer and he said, “When someone has a machine gun, we can’t fight back with bare hands.” Joint distribution came in to help around June or July 1945. The British established a displaced person camp.

On September 15, 1945, Roman took part in the Belsen Trial. He had a metal Jewish Star made which he wore throughout his time on the witness stand. He testified for three days. The defense lawyer tried to confuse him and accused him of lying. He mentioned what Josef Kramer did. In the end, he was given the death sentence.

In 1960, his friend Robert, another inmate at the camps, sued IG Farben. When he registered as part of the lawsuit, he received a letter from Frankfurt, Germany saying that he was never at that camp. About four weeks later, he received a written apology from the Red Cross that said he was there.

During the war, he saw a young girl named Jean crying. Years later he was walking with a friend and heard someone shouting his name. It was Jean! In the corner, he saw a girl with dark blond hair and deep blue eyes washing clothes. I said to his friend, “I‘m going to marry her.” His friend told him that he was crazy. After months, they dated. Roman and Masza got married on January 27, 1946.

His daughter, my maternal grandmother, Sara, was born in Bergen-Belsen in February of 1947 in the displaced persons’ camp hospital. They then moved to Rhode Island and met up with all of their friends.

In 1968, my grandmother met my grandfather, Marvin, and they quickly got engaged. Roman worked in a textile factory. In 1971, Sara bought a house in Great Neck. Roman moved to New York to work for Marvin as the manager of his medical practice. Throughout his life, he loved to throw parties and enjoy life, especially with other Holocaust survivors. As he said, “If you live for the day you have a chance for tomorrow. That is the way I lived for the two and half years in Auschwitz and all the other camps and during forced labor.”

My great-grandfather, to this day, is a very important person in my life. Even though he is no longer with us, I still think about ways that I can make him proud. I am grateful now that I get to tell his story.

Deborah J Skolnik • Oct 9, 2023 at 10:34 pm

Ava, your mother just shared this magnificent piece of writing with me. I am awed by your gift for conveying such a difficult tale with grace and humanity. I hope you will continue to enrich the world with this gift of yours.

eli sompo • Aug 1, 2022 at 7:13 pm

Thank you for the lovely story.

I guess that Roman was part of our family but I’m not sure exactly.

Maybe somewhere here

https://www.geni.com/people/Mosiek-Sompolinski/6000000031575263564?through=4137711111220010383

Jennifer Walker • May 11, 2022 at 5:56 pm

Thank. you, Ava. This is a very powerful and moving piece. It’s so important to share these stories so we never forget.

Steven Ebert • May 8, 2022 at 10:38 pm

Well done and thank you for posting!