Why Scarsdale Should Demand Affordable Housing: An Op-Ed by Jacob Rosewater

June 3, 2020

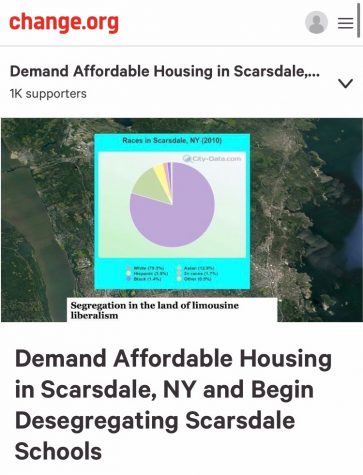

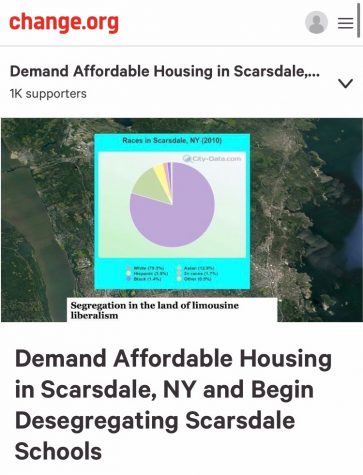

Recently, I started a change.org petition to demand that Scarsdale build new affordable housing and begin the process of ending de-facto segregation in our community. Within a day of the petition being released, it gathered over a thousand signatures. This issue has always been important to me, and over the past few years, I have tried to bring attention to Westchester County’s unaffordable housing, so it is heartwarming to see how much genuine support there is in the community. In 2018, I worked with Community Housing Innovations, a local nonprofit, and Westchester based journalists and county legislators to conduct research on affordable housing policy and exclusionary zoning laws. In 2019, I took part in a three-week summer program on urban planning at Columbia University, and in January of 2020, I interned at the (914) Cares’ First Annual Poverty Symposium, which focused on Westchester’s economic geography and policy solutions to the county’s racial and socioeconomic inequalities. Through this work, I have seen the amazing potential in affordable housing, and it has become clear to me that if Scarsdale were to build such housing, our community would grow freer, happier, and more diverse.

Since it became incorporated in 1915, Scarsdale has used exclusionary zoning laws to prevent all attempts at racial or socioeconomic integration. In her book, A Sort of Utopia: Scarsdale from 1891 to 1981, the historian Carol O’Connor explains that when Scarsdale adopted its first zoning laws in 1922, it did so with the purpose of “sealing off the community” from the rest of Westchester (O’Connor 39). This code, nicknamed a “rich man’s proposition,” sought to make it impossible for middle and lower-middle-income residents to move in (O’Connor 40-41). In fact, some of the only multifamily housing in Scarsdale – built in 1930 – came into existence only after a judge ruled that the town had “improperly rejected” the development, noting that multifamily residences represented less than half a percent of Scarsdale’s housing (Hughes).

More recently, Scarsdale has resisted attempts to create more fair and equitable housing through obstructionism and disobeying court orders. In 2009, Westchester County came to an agreement with the Obama Administration’s Department of Housing and Urban Development where the county agreed to “create hundreds of houses and apartments for moderate-income people in overwhelmingly white communities [including Scarsdale] and aggressively market them to nonwhites in Westchester” (S. Roberts). At the time, the Obama Administration ordered that Westchester conduct a zoning report on exclusionary zoning practices that affected the demographics of the county. As I learned three years ago when I interviewed Alec Roberts of Community Housing Innovations, “Scarsdale, a town that exemplifies exclusionary zoning policies, has, as a result of its resistance to affordable housing… prevented people from moving in for being part of specific groups… both in terms of class and race” (A. Roberts). Nonetheless, Westchester’s former county executive Rob Astorino (R), had his administration publish a zoning report claiming that there were no exclusionary zoning practices in Westchester County (WNYC). This report, rejected by the Obama Administration ten times for its questionable analysis, was finally accepted in 2017 when the Trump administration decided to ignore exclusionary zoning in their assessment of Westchester’s affordable housing practices (WNYC).

As a result of Scarsdale’s history of classist and racist exclusionary zoning policies, our community has become incredibly homogenous. Scarsdale is 77% white, nearly 21% above the New York State average. Asian Americans, the other major demographic group in Scarsdale, have a population of only 5% above the state average, and the African-American and Latinx-American populations are 15% and 13% lower than the state average respectively (Statistical Atlas). Scarsdale’s 2016-17 senior class was only 2% African-American and Latinx-American (NYSED). Although the situation has somewhat improved, with Latinx-American students representing 8% of the 2019-20 senior class (compared to the 27% state average), it is still worth noting that among Scarsdale’s Hispanic population, only 14% would be considered “non-white” (Statistical Atlas).

By getting serious about affordable housing and exclusionary zoning in Scarsdale, the village government would be able to create a more diverse and prosperous community. As a result of Scarsdale’s exclusionary zoning practices, we have let our town become a homogenous mostly-white enclave, and have allowed for “a net loss of over 50% of [our] young population aged 25-34… leading to a loss of economic growth in [our] community” (A. Roberts). Further, despite the popular belief that affordable housing suppresses property values, this is not the case. In 2017, researchers at New York University conducted a study on the impact that affordable housing has on property values. After looking at the data, they concluded that affordable housing does “not suppress property values, and may even raise them” (NYU Furman Center). There are no downsides to building new affordable housing in Scarsdale. In order to integrate our community, create economic growth, raise property values, and fight systemic inequality, Scarsdale ought to embrace affordable housing and reject the exclusionary zoning that has defined the last hundred years of its history.

To sign the petition, click here.