The Race Project

December 8, 2017

In the seventh grade, I built my Wii Mii with white skin and blue eyes. I was trained to see white as beautiful. Most days now, I am proud of my race, but “you’re pretty for an Indian” follows me.

I am somewhere between feeling proud and feeling unsettled. I am learning just to be proud.

Right now, I’m recognizing that my skin color is how I’m usually first characterized. My race has never been the first thing I see in the mirror, so I’m learning to not feel strange when others refer to me as “that Indian girl.”

I think we are all learning to be proud of our race and where we come from.

When an editor proposed that Maroon discuss race, I got nervous. There was no escaping my visceral thought: I’m not qualified to discuss this.

I’ve never experienced racial discrimination. My skin tone has handed me white privilege. Who am I to write on behalf of others? How can I discuss a topic I know little about?

Students of all racial backgrounds are uncomfortable discussing race; it’s a sensitive subject, and many would rather stay quiet than risk offending others.

The racial slurs directed towards a White Plains security guard from a car with a Scarsdale bumper sticker were likely motivated by cruel humor. But Maroon staff refuse to recognize this incident as one isolated exchange.

For the past few months, we have listened to students and staff speak about how race plays a role in the discussions and relationships in this building.

Race impacts everyone, and we can’t have a full discussion when there are still voices missing from the conversation. Whether we realize it or not, race impacts our daily interactions, from who we choose to have as friends to how we subconsciously perceive strangers. If we wish to make our community more inclusive and to begin to combat injustice, we must be able to discuss race transparently and succinctly; to do that, we can’t let fear prevent us from talking.

In the following pages, we will present a number of perspectives from students who were willing to open up a dialogue. Each story is unique and does not necessarily represent a larger experience—and that’s intentional. No one story is more valid than another.

If you, like many, feel uncomfortable discussing race, remember that a conversation requires multiple voices. It’s your turn to speak.

-Sneha Dey and Emily Kopp

We invite you to send comments and letters to the editor to our email, [email protected] .

by Maya Bharara, Caroline Meyer, Talia Potters and Ali Rothberg

“I’m surprised you are so articulate!” “Are you sure you can afford that?” “Your dad is a doctor?” “You live in Scarsdale? Really, you?”

Although most SHS students have never had these questions and comments directed at them, they are not uncommon for Imani Nwokeji ’18. As one of only a handful of black students at SHS, issues of race are constantly on the forefront of Nwokeji’s mind.

Before going shopping, Imani Nwokeji ’18 makes sure her hair is straightened, her clothes are ironed, her makeup is flawless, and her handbag matches her shoes. While many girls undertake this process before going out for the sake of being “girly,” Nwokeji’s reasoning is also rooted in racial worth. “If I go to a store, I need to prove myself and have a nice bag on and have my hair done and makeup done so I give this vibe that I have something,” commented Nwokeji. While many people might be used to cruising the grocery store in sweats, Nwokeji, no matter where she goes, must remain conscious of her appearance and behavior in order to avoid being persecuted as what some would regard as the black person that steals or exhibits other criminal behaviors.

Yet this was not always the case. Growing up in an urban neighborhood in the Bronx, she was constantly surrounded by people of all races—blacks, whites, Asians, Hispanics, and other ethnicities coexisted and integrated relatively peacefully. Nwokeji was never cognizant of race because seeing people of all different shapes, sizes, and colors was completely normal to her. “I didn’t realize my race until I looked at Scarsdale and realized that I am a little darker, my hair is a little curlier, and I started to notice my race,” reflected Nwokeji. “It was just different when you go from something that’s so racially [diverse] to something so white and… you [become one of the] only black girls in that school.” Nowadays, race continues to cross her mind in terms of facing stereotypes and preventing herself from being assigned unfair labels. She constantly has to be aware of how she acts so as not to come across as aggressive and vulgar. “I have to make sure I’m not portrayed as the angry black woman. It’s not a nice label to have.”

Growing up and exploring her race in a predominantly white neighborhood has contributed to Nwokeji’s consciousness of her race. Socially, a challenge Nwokeji has faced is getting her peers to view her as a person with complexities beyond her race. “ “I think that some people that don’t know me just see me as that black girl. I’m Imani, there’s more to me,” commented Nwokeji. “I think that until people become closer friends with me they can’t see beyond [my race].” In academic settings, Nwokeji is credited by others as having an expansive knowledge of all things race-related. When discussing race in her history and English classes, her classmates and even teachers sometimes look to her to be a spokesperson for the entire black community, which can be awkward and uncomfortable. “I don’t like speaking for my race because everyone in every race has different opinions. I don’t speak for all black people, I speak for myself,” she said.

Occasionally classroom discussions and commentary can turn out to be downright insensitive or racist. But because she is afraid of coming off as disrespectful or having a teacher retaliate against her through her grade, she must choose when she feels the need to respond to an injustice. During her junior year, Nwokeji was playing a review game in class when her class began to joke that she was cheating. As a way to join in, the teacher laughed about how the class “would have to hang Imani” if the cheating continued. As a black person, allusions to lynching are all too real and terrifying, thus prompting Imani to freeze when the comment was made. Furthermore, she was too afraid and uncomfortable to speak out against the teacher’s comment and get help. “I reported it to [a teacher] in the middle of the year and he spoke to her. I didn’t go to my dean but I really wanted to, I should have,” reflected Nwokeji. Still, she regrets letting her fear of speaking up for herself directly get in the way of her taking charge against the insensitive comment.

Dealing with racism, being bombarded with negative stereotypes of blacks in the media, and feeling the need to constantly prove her intelligence and socioeconomic status is something Nwokeji has had to face for most of her time in Scarsdale. Nevertheless, she is proud of her race and the community it has built for her. She hopes to use her experiences to help uplift other black people by encouraging education and to help build a better understanding of race within the community.

![]()

“Sometimes… [I don’t] exactly feel that I fit in, but I don’t feel left out either,” explained Joao Pedro De Mello ’19, a Latino student who says his Brazilian background influences his daily life. For starters, he has had to master two different languages: Portuguese for his family and English for school, and he explained how this perpetual flip-flop is a constant reminder that he is different from his peers. In Spanish class, De Mello hears comments implying that his work is less valid or meaningful than his peers’ work because he comes from a Latin American country—despite the fact that he grew up speaking no more Spanish than his fellow students did.

“I’ve chosen to ignore that negativity and… I’m not ashamed of who I am.” He’s heard insensitive racial and ethnic jokes in hallways and thinks that many people in Scarsdale are “shielded” and therefore unable to discern what is and is not offensive to a person of color. “[Students] will just say [offensive things] because they think… no negative impact can come from it.”

When discussing Trump’s comments on Latinos and Mexicans, De Mello explained that he could not “understand why [Trump] has… such a burning hate for [a stereotype] that isn’t necessarily true.” He was also upset by the current administration’s undoing of past legislation to help undocumented Americans like DACA. “I think that [people of] my [ethnicity] are viewed as working class laborers,” De Mello elaborated, and he explained that this stereotype exists even at SHS. He feels that the discussion of Latin America and Latinos in classrooms is lacking, and he “wants to learn more about the place I’m from and how [my country] impacted the world.”

Although De Mello stated that he believed being white would make him feel more safe, he treasures the Brazilian community in Scarsdale. “[The community] helps bring back old memories and [prevents us from] forgetting our heritage,” he said. “I’m proud of where I’m from!”

![]()

When Sean Michael ’19 was in elementary school, he did not think he was different. It was not until sixth grade that he realized that he was black—until then, being surrounded by white and Asian people led him to believe he was just like them. “I called peach ‘skin color’ because everyone else did, even though it wasn’t my skin color—they weren’t the same at all,” he explained. How often do you think about your race?

While the SHS community is generally accepting of his race, there have been times students’ responses to Michael’s race led to uncomfortable situations. In elementary and middle school, people would think they had permission to touch his hair “after I got a haircut and it was super spiky, even though I felt really uncomfortable with that.” There have also been numerous instances in which friends casually used the n-word or told racially offensive jokes. “There are people who said the n-word just willy-nilly in middle school, and I kind of had an issue with that,” Michael explained. As for racist jokes, “in middle school, people said them in my presence. And here in the [high school] library especially, I’ve heard people telling them.” As for classroom experiences, Michael felt somewhat singled out during the tenth grade To Kill a Mockingbird unit. Though no one explicitly said anything, he could tell people expected him to comment on racial issues. “I guess it’s fair, but I don’t always have super strong opinions about these topics,” he said.

Nowadays, though Michael is of course aware of his race, he only occasionally thinks about it unless something forces him to consider “‘Oh, how is this going to reflect on me? How are people going to view me?’” Though he doesn’t believe people at SHS think he is just like African Americans they may read about in the news, people “are most likely judging me in a different light based on what other people of my race have done, and depending on how publicized that’s been, the effect might be of various magnitudes.” Ultimately, though, Michael feels safe in Scarsdale, and believes that, for the most part, people at SHS do not judge him by his race.

by Evan Huo

The lack of Asian athletes in professional basketball means that many immediately perceive me as a poor basketball player. This leads to a perpetual underdog status. However, being an underdog is not always a bad thing. I love to see the shock in other’s faces when I exceed their initial expectations. On the other hand, I feel as if I have to represent the entire Asian basketball community every time I play, as I am often the only Asian basketball player on a team. Being the “token Asian” can have its perks: the coaches always remember your performance and know who you are. However, they may not know you by your real name but rather an insensitive nickname: I’m frequently dubbed “Yao” or “Jeremy.” Perhaps one would think this is intended as a compliment, as I am being compared to great basketball players, but even strangers who have never seen me play have called me similar names.

Most of my teammates and coaches have been accepting of me, and I’m fortunate that I rarely feel as though I am treated differently because of my race. With that said, there were two instances that angered me. When I was trying out for JV basketball as a freshman, there was a junior who I had held in very high regard. One day, during an early morning workout, he told me that next week I should bring “lo-mein noodles.” Although a very mild comment, everyone in the room busted out with genuine laughter. I was furious, but I did not stand up for myself because I was scared that the varsity team would think less of me. Another time, my friend invited me to play basketball with his friends from B’nai B’rith Youth Organization (BBYO). During the game, one of the BBYO members said my dad probably owned a laundromat and wanted to know the name of the store. That night, as I sobbed in anger, I wondered why a person who belonged to another persecuted group was saying such offensive things to me.

I believe that this insensitivity goes beyond basketball. Because of America’s history of slavery and current heightened tensions, it is seen as more politically incorrect to be offensive towards African Americans than Asian Americans. For example, if I were to call a black basketball player “LeBron” or “Kobe” solely based on his/her race, it would likely be viewed with more hostility. The mainstream media portrays Asians as passive people, and in retrospect, I regret not standing up for myself, as I was only perpetuating that stereotype.

If I could give my younger self one piece of advice, it would be to stop trying to fit in with my peers, and realize that I am not the same as them. However, my uniqueness should not be viewed as a flaw and I should learn to embrace it, rather than masking it like refusing to learn Mandarin. As I’ve grown older, I have finally accepted my identity as an Asian American and I would not change it for anything.

“That was the first time anyone has ever called me the N-word,” said White Plains High School security guard Sonya Smith. In early September 2017, the SHS community was stunned when Smith reported that a group of students had shouted racial slurs at her following a football game.

The students sped off in a car with Scarsdale decals. Two weeks later, discriminatory phrases were spray painted by a Clarkstown student on the paddle ball courts at SHS. The vandalism consisted of a homophobic slur, the letters “K.K.K.,” and depictions of male genitalia. “Most of us here at SHS want to be inclusive and cultivate an environment where people feel safe and feel like they belong… But I do think there are kids who struggle with racist and offensive ideas and thoughts, and at times they target others,” said SHS Assistant Principal Dr. Chris Griffin.

Even though a classroom should be the safest place to discuss race, students still struggle with what and how it is discussed.

Why we need to talk about race

“I think it is important to discuss race here [in Scarsdale] for the same reason it is important to discuss race everywhere: because we are part of the organism that we call our country, and so we need to be connected to that conversation,” said SHS history teacher Maria Valentin. SHS Social Studies Department Chair John Harrison shared a similar sentiment: “I believe that in a world that is riddled with intolerance, the more we can talk about who we are as people and how we fit into the larger globe—religiously, culturally, and racially—the more we make the world a better place to live in.” Race is a constantly changing topic, and certain racial events may fuel discussions. The main goal of teaching about racial conflict is to inform the student body about the history of race relations, to connect to current issues, and to think carefully about how to talk about race.

Teachers at SHS feel a responsibility to remind the student body to be sensitive, informed, and willing to discuss racial issues open and honestly. “It’s not just a white cop shooting a black guy [or] a neo-Nazi at a rally in Charlottesville getting violent. It permeates everything and everywhere in a profound way. To not address the importance of that or the cultural context of that is to not responsibly educate the students here,” said SHS English teacher Wes Phillipson.

But what happens when the N-word appears in an article, document, or work of literature in a history or English class?

Some students cringe. Others blush. A few shrug.

However uncomfortable a class is, students cannot avoid encountering the word. “The N-word is certainly part of the American history narrative, as it is part of the American literary world, and it needs to be talked about and discussed and not avoided,” said Harrison. Moreover, though vulgar, racist, and reprehensible, the N-word is still widely used, especially in social media and popular culture, as an informal greeting or even a friendly name. This shift can cause us to forget the word’s history as a vehicle of oppression and only further confirms why we must discuss racial issues in classrooms.

How we talk about race

History classes cover many race-related topics, such as imperialism, globalization, and the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, while English classes confront race through texts and literature, reading books such as To Kill a Mockingbird, Huckleberry Finn, and the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.

When the N-word appears in literature, some teachers avoid saying the word altogether. “I myself don’t say the word because when I teach it, I want to make sure that I’m trying to be as sensitive as possible. [I also want to] model ways to work around the word as a white person who doesn’t presume that I have any right to say it,” said SHS English Department Chair Karine Schaefer. She believes that it is essential to educate people on what the word means in America, including the history of the N-word and why the word is such a spiteful term. Some students also believe that the N-word should never be used in the classroom under any circumstances. “For the N-word to be used by just anyone takes away the meaning of the word. It’s not okay for teachers to be setting this example,” said Jenny Liu ’19. Some students feel that when teachers use the N-word, they are promoting acceptance of the word.

On the other hand, some teachers and students fear that avoiding the use of the N-word is doing a disservice to students by taking away from the suffering associated with the word’s history. Retired SHS history teacher Rashid Silvera, who taught Race and Ethnicity for many years, feels as though not addressing the word “sanitizes” the issue and “unfairly lessens a person’s perception of the pain and enduring damage to the intended victim.” Christine Lambert ’19 believes that teachers need to address the N-word if it is going to appear in a class reading. If the N-word is not actually said, the meaning and significance that the word carries is not conveyed.

SHS English teacher Jennifer Rosenzweig gets input from her students before introducing the N-word because she thinks that “people are just really quiet and uncomfortable.” She presents her junior class with an anonymous survey asking how they would like to handle the word’s appearance in books they are reading. “In both of my junior classes, a half to two thirds of the kids said we should say it … At least a third of the kids said that they prefer not to use it at all.”

Although many—perhaps all—of the faculty agree that teaching about problems that stem from race should occur whenever appropriate, teaching methods vary. In regard to how teachers teach these units, the administration does not dictate an exact method they must use in the classroom, giving teachers the liberty to address race, including the usage of the N-word, however they see fit.

Discomfort talking about race

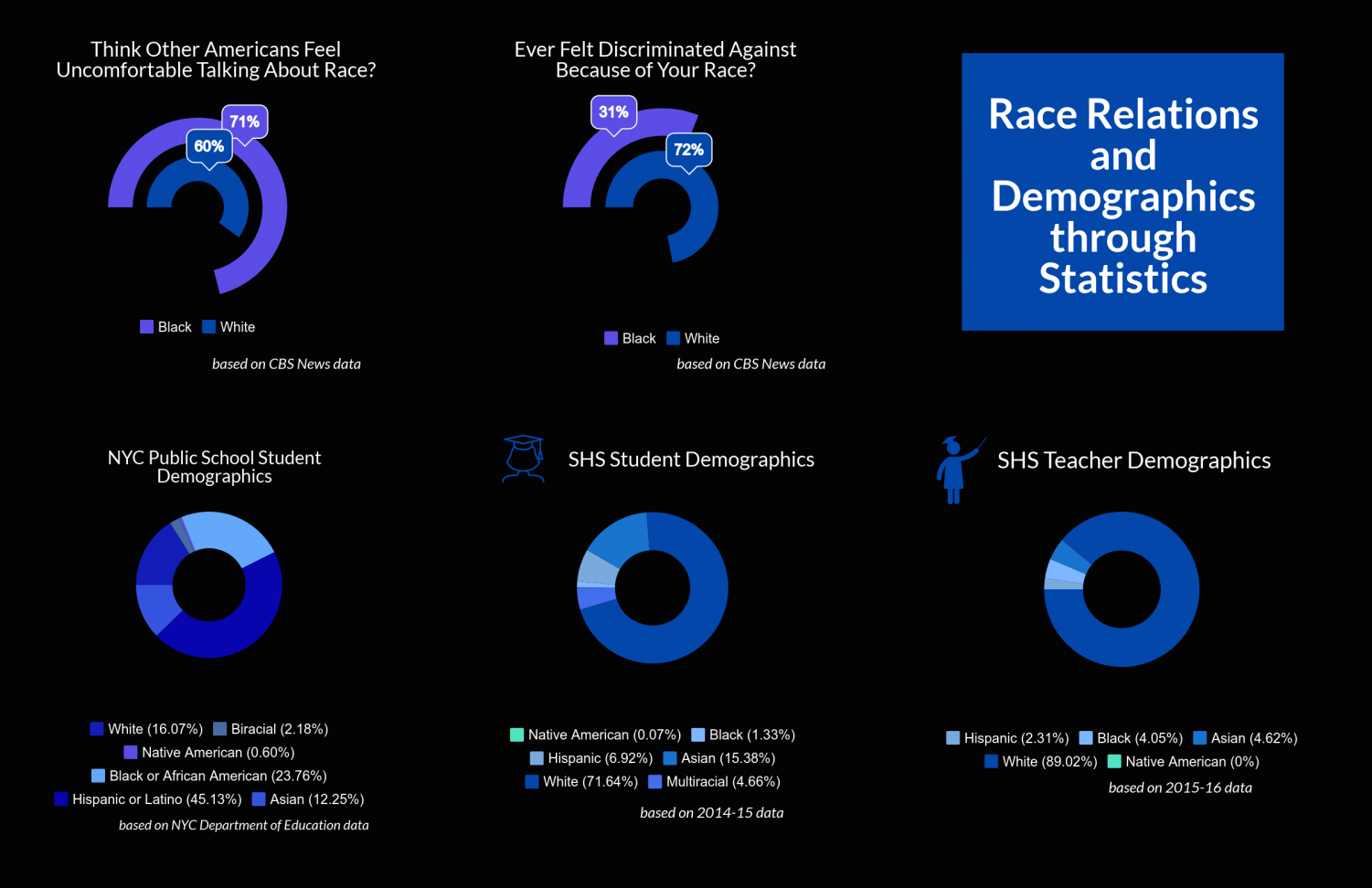

Many Americans find talking about race to be difficult. According to The Atlantic, eighty percent of millennials would prefer not to discuss it. Furthermore, a majority of white and black adults say they feel uncomfortable exploring the subject with someone of another race. SHS students are no different, resulting in sometimes lackluster classroom discussions on what can be a volatile topic.

Students and teachers alike agree that at times, the topic of race leads to uncomfortable conversations. Some students may feel that they are not in a place to speak on certain issues. “In most of the classes that I’ve been in, when we’ve had a [racial] discussion, the majority (if not all) of the students are white or Asian… I feel unqualified and privileged,” said Julia Levy ’18. Other students fear accidentally offending classmates with a comment or question. “I generally like to be the last one to speak because I think it’s a good idea to listen first and then speak knowing the opinions of other students,” remarked Samantha Lawless ’18.

SHS English teacher Stacey Dawes acknowledged that “there is a discomfort for students to talk about race when someone in the group is of a different race,” which can lead to minimal and reluctant participation. Others may feel uncomfortable with their race’s role in history, leading to denial. “I think [it’s] unfortunate… that white people… as the historical oppressors, can’t come to terms with race and racism and make sense of it,” said Phillipson. Beyond mere denial, this discomfort can cause students to behave disrespectfully in an attempt to disengage. “When we’re discussing the issue of slavery, and people are chit-chatting or on their phones and not paying attention to the teacher—I think for an issue like that… people should be paying attention,” said Adeye Jean-Baptiste ’19.

Talking about racially-charged situations in class can be difficult for African-American students, too. “Almost always, I’m the only black kid in the class… Sometimes I feel a little awkward, but it’s not due to anyone in the class. It just naturally comes,” said Chris Gaujean ’18. Other students of color have also experienced the discomfort of being the only person of their race in a class, as there are relatively few minority students in Scarsdale. Some of these students may feel pressure to represent the views of their entire race. Jean-Baptiste often feels silenced and isolated when only one percent of SHS is African American. “In many cases, I am the only African American in the class which makes it hard because there’s no one there to back me up and confirm that what I’m saying is valid,” said Jean-Baptiste.

Even though these conversations are uncomfortable for many, regardless of their race, they are necessary to achieve a teacher’s ultimate goals: the broadening of students’ worldviews and the acceptance of others. The more race is spoken about, and the more comfortable we are with discussions on it, the more students will be able to combat racism outside of the classroom.

Invisibility of non-black people of color

Non-black people of color often feel like lessons about their race receive less attention in classroom discussions and curricula. Students learn about Latin American revolutions in sophomore history, but “it’s never [talked about] to an extent that you can actually depict the full picture of it,” explained Joao-Pedro De Mello ’19.

Discussions are often focused on black and white race-relations. “It’s reflective of our country’s history. When has our politics ever been about Asian people? [We just] stick Japanese people in internment camps and call it a day,” said Zoe Landless ’18. De Mello wishes Latino history was discussed to the extent it deserves. “It sometimes annoys me because I do want to learn more about the places where I’m from and how [those places] impacted the world,” stated De Mello.

Jolie Suchin ’18 notes that the only representation of Filipinos in the media has to do with current Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, saying “I hope [he] doesn’t represent what the Philippines stand for.” She believes her classmates would benefit from discussing Filipino history, to combat the distorted way Filipinos are portrayed. “Whenever we do talk about the Philippines, it’s always about how the U.S. annexed them… Without being half-Filipina, I wouldn’t know anything about the Philippines. That’s sad for me [to think about].”

Some students claim the lack of Latino American and Asian American history may lead to more ignorance among fellow students. “I have heard a few of my white friends say that racism doesn’t exist anymore, and so they’re very oblivious to the race issues that exist outside of where we live. We should at least talk about [minority races] to decrease the ignorance towards other races,” commented Megumi Ohara ’19. Some social studies teachers dispute such characterizations. “We have over the last 20 years made a deliberate effort to bring in the non-Western narratives and give them a large place in our curriculum. The frequency and the opportunity to talk about race increases when you embrace a more global perspective,” said Harrison.

—————

Given the tumultuous history of race in our country, racial issues such as the Charlottesville confrontation and the Black Lives Matter movement will continue to be a topic of conversation in the classroom. These events often feel distant from our Scarsdale community and therefore go unacknowledged by the white majority here. But racial tension does exist in our community. Both white and minority students feel uncomfortable talking about race, a manifestation of the discomfort we deal with every day. The Scarsdale classroom gives students a safe and enriching environment to talk about race. If we are not fully utilizing this resource, we will remain uncomfortable with the topic. If we are able to discuss this difficult topic more adequately, we will create a generation of citizens who are better informed and willing to find solutions to racial conflicts in Scarsdale and beyond.

Reporting by Jacob Faireman, Carly Kessler, and Max Yang

![]()

Scarsdale has many white and Asian students but startlingly few members of other racial and ethnic groups. Our relatively homogenous population affects the views and beliefs of our community and negatively impacts the school environment. In a community so focused on education, we need to acknowledge and compensate for this gap.

Homogeneity limits both our knowledge and empathy. Events and ideas distant from our own experiences do not always stick. In a community with a Jewish plurality, learning about the Holocaust is rightly an emotional experience for both Jews and non-Jews alike: the event’s direct impact on many Scarsdalians makes connecting to it easier. However, we often lack this emotional response to issues more distant from our community. When learning about slavery in U.S. History, we lack a depth of understanding that more African-American voices might provide. We want to understand how people of all nations, races, and ethnicities felt at different points in history; we want to understand what they endured and how they overcame, in part so we may learn from the past. But without a personal connection to invoke empathy, we are not always able to do so.

Because we cannot connect to stories distant from our own, we often approach our consideration of history from a Western perspective, too often ignoring the whole, multiracial story of our nation. In doing so, we further damage our ability to see a group of people as more than an easily stereotyped collective, but rather as the individuals—with unique characters and stories—that they are.

The lack of diversity at SHS also inspires an inherent comfort in homogeneity. There is often unease when discussing race in school, and in both class and more informal social environments, students resort to jokes—sometimes offensive ones—in attempts to relieve tension. Our community’s lack of diversity also causes many SHS students to seek environments similar to Scarsdale in college and even later in life. Increasing numbers of SHS graduates move back to Scarsdale as adults, in part, of course, for the schools. But are some so scared of the unfamiliar that they attempt to avoid it altogether by embracing the bubble?

Scarsdale has attempted to increase diversity, but there has not been enough success. The Student Transfer Education Program (S.T.E.P.) enables minority students from underprivileged communities to attend Scarsdale schools, but only two students are brought to SHS each year. In 1968, the same year that S.T.E.P. was created, there was a proposal to bus African American students from Mount Vernon to Scarsdale. Those who supported the plan believed it would give both schools exposure to different communities with different racial compositions. According to the Scarsdale district website, those who opposed it “worried about eroding educational quality and property values.” While Scarsdale voted to approve the plan, it was ultimately rejected by Mt. Vernon — and no new diversity program has been proposed in the forty years since.

Even without full integration, we could still create a “sister school” program to spark connections with people in Westchester from whom we might otherwise feel distant. We need to understand how the racial composition of our school and community affects our view of the world, and notice too how that view affects the historical narrative upon which we focus. Only with self-awareness will Scarsdale be able to work toward becoming the socially liberal community it claims to be.

This article was edited on March 8, 2023.